Scaling Python Web Applications: AsyncIO vs Threads

It started with a tweet

Recently, Mike Bayer tweeted:

I can't stress enough what a bad idea it is to build out a database application architecture on top of a non-blocking IO approach, that is, asyncio, eventlet, gevent, etc. 1/

— mike bayer (@zzzeek) May 31, 2019

Needless to say, I strongly disagree.

While, “database application” is a pretty broad category to designate not using AsyncIO for, I wrote a framework that lives in this category: Guillotina.

Also, there are many great projects that are designed specifically for AsyncIO and seem to perform extremely well–just look at all the things the magicstack people are doing with EdgeDb.

I had quite a few responses to the tweet and I’ll try to expand on those things in this post.

CPU Bound

Mike stresses that AsyncIO breaks down when you have CPU bound code. I do not disagree. I have

always advised that you should never have CPU bound code in AsyncIO and if you do, make sure

to use run_in_executor. Even then, it’s not ideal and you should think about solving your

problem another way(queue, another services, etc).

Threads can be CPU bound too

The point I want to touch on here is that being CPU-bound is not an AsyncIO only problem. You can be CPU-bound with threaded web applications as well.

Let’s see how a thread-based application performs vs an AsyncIO applications for CPU bound request handling.

For the context of this post, we will be using this loader script. It defaults to running 100 requests concurrently.

Our simple CPU bound threaded app will be a flask app that does a CPU heavy task for half a second on each request:

from flask import Flask

import time

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/')

def cpu_bound():

start = time.time()

while True:

9 * 9

if (time.time() - start) > 0.5:

break

return 'done'

Run using ./bin/gunicorn -b localhost:8080 cpu_bound_flask:app

And the same app, done with aiohttp would look like this:

from aiohttp import web

import time

async def hello(request):

start = time.time()

while True:

9 * 9

if (time.time() - start) > 0.5:

break

return web.Response(text="done")

app = web.Application()

app.add_routes([web.get('/', hello)])

if __name__ == '__main__':

web.run_app(app)

And we’ll also provide an aiohttp version that uses threads

for the CPU bound code using run_in_executor:

import asyncio

import time

from aiohttp import web

def cpu_bound():

start = time.time()

while True:

9 * 9

if (time.time() - start) > 0.5:

break

async def hello(request):

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

await loop.run_in_executor(None, cpu_bound)

return web.Response(text="done")

app = web.Application()

app.add_routes([web.get('/', hello)])

if __name__ == '__main__':

web.run_app(app)

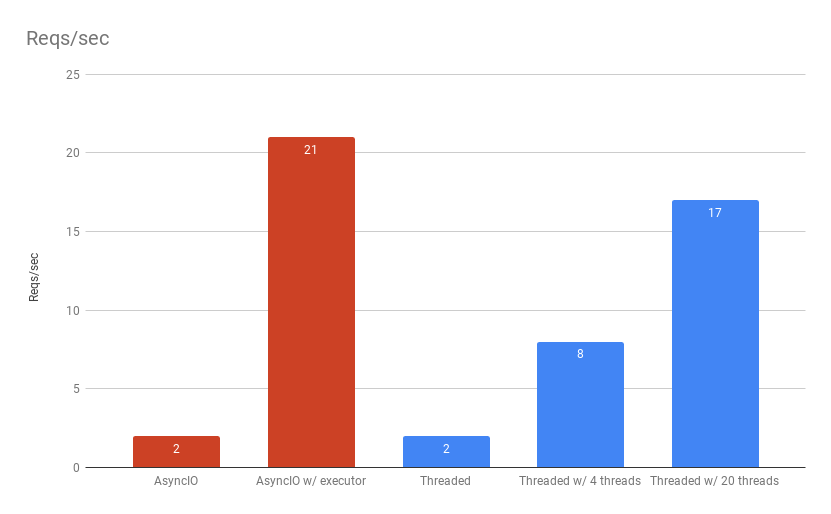

Threaded vs AsyncIO Results

AsyncIO

AsyncIO predictably performs at 2/requests/second. This is because AsyncIO is single threaded. If your one thread is constantly occupied, it will not be able to service other requests.

1 thread x 0.5 seconds = 2 requests/second

AsyncIO with thread executor

The AsyncIO thread executor variant with results are a less easy to predict but we can try. We are using the default thread pool executor which, from the docs, says:

will default to the number of processors on the machine, multiplied by 5

For me, I have 4 cores on this machine:

4 cores x 5 x 0.5 seconds = 40 requests/second

But wait! In the results, we only obtained around 20 requests/second here. I didn’t investigate why we didn’t get up to 40 requests/second but can only guess that it has something to do with python threading just not being very fast and limits to what 4 cores can do in general along with other things running on my computer. Generally, if you want to maximize python performance, you want to limit the number of CPU-bound threads per process you are using. This is true for any python application.

Threaded flask

Finally, the flask app actually performed worse than I expected with out of the box

documentation for how to run it in production with gunicorn.

I was surprised to find out gunicorn defaults to being single-threaded–maybe there

is a lesson in that for performance.

Other than that, flask still performed predictably for the number of threads it was configured to handle.

It was also interesting to see that AsyncIO with run_in_executor performed better than gunicorn with 20 threads.

I included results using a different gunicorn threads setting to be able to match what is happening with the number of threads run_in_executor is using with AsyncIO.

Worst case

As Mike Bayer mentioned on the Twitter, the worse case scenario with AsyncIO is when you have a lot of CPU bound code and your application starts performing so poorly that it can’t even schedule and respond to network IO properly:

no you don't, you don't have database connections being dropped by the DB because the app was hung and couldnt respond to a ping or an authentication challenge. The OS schedules tasks way more effectively than the way your app happens to use IO

— mike bayer (@zzzeek) June 2, 2019

He is correct. If your AsyncIO application has a lot of CPU bound code that is binding the event loop from operating, you will have problems–potentially very difficult problems to diagnose. These types are issues are less likely to happen with threaded applications because the operating system can schedule running threads regardless of your application being CPU bound.

Read up on AsyncIO development for tips on understanding how to deal with and avoid this.

Network IO Bound

Now where AsyncIO really shines and threaded apps really struggle is with network bound operations.

Most web applications, especially in micro-service frameworks, are network-IO bound. The main point of micro-service frameworks is small services that speak http. If you are blocking when interacting with other services, your performance will dramatically suffer.

Setup

For the sake of our test, I’ve created a simple slow service that each application will communicate with to demonstrate the scenario:

from aiohttp import web

import asyncio

async def hello(request):

await asyncio.sleep(0.5)

return web.Response(text='done')

app = web.Application()

app.add_routes([web.get('/', hello)])

if __name__ == '__main__':

web.run_app(app, port=8081)

The service simply does a sleep for half a second and then returns. This is simulating the half second delay like we did with the CPU bound case.

Our flask app:

from flask import Flask

import requests

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/')

def io_bound():

resp = requests.get('http://localhost:8081')

return resp.text

run using ./bin/gunicorn -b localhost:8080 io_bound_flask:app.

And the aiohttp app:

from aiohttp import web

import aiohttp

async def hello(request):

try:

session = app.session

except AttributeError:

session = app.session = aiohttp.ClientSession()

async with session.get(

'http://localhost:8081') as resp:

return web.Response(text=await resp.text())

app = web.Application()

app.add_routes([web.get('/', hello)])

if __name__ == '__main__':

web.run_app(app)

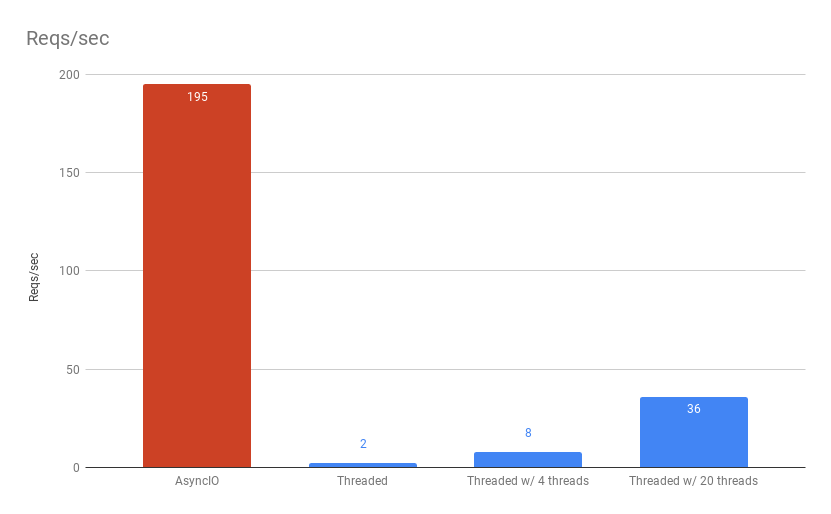

Threaded vs AsyncIO Results

AsyncIO

Here we can see how AsyncIO can perform well when you are connecting to slow services. The application is single threaded; however, it is not io-bound.

It could perform even better; however, it is simply restricted to the concurrency setting we used for the tests(100).

1 thread x 0.5 seconds x 100 concurrent ~= 200 requests/second

Threaded flask

Finally, the flask app performed about the same as the CPU bound example.

Unfortunately, now the flask app is blocking when the CPU isn’t even doing anything.

Summary

As with most technology, you just need to understand the tradeoffs you’re making and the consequences of them.

You definitely do not want to have CPU bound AsyncIO applications. Also, if the domain logic of your web application is rather CPU-intense(or could be some day), it probably will start performing badly.

However, thread-based Python web applications can be CPU bound as well and suffer similar performance issues in these scenarios.

In network-io bound scenarios, AsyncIO really shines. If you are communicating with many other services, you might want to look into using AsyncIO.

Tips on deploying and scaling Python web applications

Python isn’t fast. That is a tradeoff we all made when we started using it. It can be scaled though and there are a lot of very large sites that run python fine.

This blog post is already too long but here are some parting tips to keep in mind when scaling web applications:

- load balancers: Run your application with multiple processes and use a load balancer to share traffic between them.

- cpu monitoring: Make sure your application isn’t maxed out on CPU. Even better, if you’re using kubernetes(or something similar), setup auto scalers when CPU hits thresholds.

- connection pooling: Prevent simultaneous connections to python applications by using proxies/load balancers that will pool requests in front of your application to ensure your application is servicing a healthy number of requests at a time.

- message queues: if you have CPU bound tasks, put them in a queue to be processed by another service. If you have a threaded application and have a lot of network-bound io, you might also want to use a message queue for that

- micro-services; if you are using AsyncIO, you can leverage micro-services to off-load potentially CPU-bound operations.

- caching: the topic is so broad and so many ways to do it…